These days, gift-giving is too much about cursors and clicks to cart. Material goods bought with plastic shipped to porches by UPS.

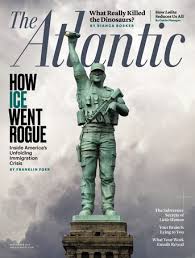

You don’t need to be a poet, however, to give a better gift to someone you love: declamation. This came to mind while reading the May 2020 issue of The Atlantic. In a piece called “Being Friends with Philip Roth” by Benjamin Taylor, the latter mentions Roth’s 74th birthday party.

Apparently Roth turned to the assembled guests and, casual as all get-out, asked if anyone cared to recite a poem from memory. As if that was still done. As if each guest had brought a poem gift-wrapped in their brain pan.

To kick things off, Roth recited a Mark Strand poem: “Keeping Things Whole.” According to Taylor, Roth “then looks at me as if to say, ‘Your serve.'” Luckily, Taylor was able to return volley. He recited Robert Frost’s lesser known poem “I Could Give All to Time.”

Roth was so impressed that he brought it up on the phone the next morning: “Those rhymes!” he said to Taylor. “It’s as if nature made them.”

And, at the time, I thought, how cool. Shouldn’t this happen more often? Not just between writers of poetry, but between readers of poetry, too?

Anyway, it was enough to set me to the task of memorizing both, starting with the easier—the Strand piece. So here’s to Philip and Benjamin.

Oh. And Mark and Robert, too!

Keeping Things Whole

Mark Strand

In a field

I am the absence

of field.

This is

always the case.

Wherever I am

I am what is missing.

When I walk

I part the air

and always

the air moves in

to fill the spaces

where my body’s been.

We all have reasons

for moving.

I move

to keep things whole.

I Could Give All to Time

Robert Frost

To Time it never seems that he is brave

To set himself against the peaks of snow

To lay them level with the running wave,

Nor is he overjoyed when they lie low,

But only grave, contemplative and grave.

What now is inland shall be ocean isle,

Then eddies playing round a sunken reef

Like the curl at the corner of a smile;

And I could share Time’s lack of joy or grief

At such a planetary change of style.

I could give all to Time except – except

What I myself have held. But why declare

The things forbidden that while the Customs slept

I have crossed to Safety with? For I am There,

And what I would not part with I have kept.