When you first begin the task of choosing poems for a poetry reading, it’s like walking into a grocery store’s cereal aisle where the choices are so vast they overwhelm the shopper.

In the case of poetry, do you choose funny poems or contemplative poems, fancy poems or simple poems, poems with sound devices or ones with narrative merits? Maybe a little of everything, you might advise, but a lot rides on the locale and the audience.

For me, tonight, the venue is a public library — a place that I hope will host many events like this in the future. Anyway, here’s the line-up card for tonight’s reading along with a little bit of the reasoning behind it:

- “Provide, Provide” (from The Indifferent World) Like Frost, whose title I borrowed, I write a lot about nature. This is a nice, solid, short poem to reflect that.

- “Simplicity” (from The Indifferent World) From Frost, I will move to another icon who has influenced by work, Henry David Thoreau. This poem pays homage to an important concept in his book Walden.

- “Return of the Native” (from The Indifferent World) A little twist for #3, this work is straight out of the imagination — one that couples ghosts with a whaler captain’s house along the New England shoreline. You know they’re in there!

- “Mrs. Galway Goes to Night School” (from The Indifferent World) By poem #4, the crowd will be ready for a little narrative poem about a school bus driver going to night school for Irish Literature. James Joyce, this one’s for you! And Mom, you, too!

- “Barnstorming the Universe” (from The Indifferent World) Back to the imagination, this one’s a fanciful work based on a Maine barn that looks like it experienced a crash landing from outer space. It’s a real barn, one I run by each summer morning. A postcard poem, then, with hyperbole for a return address.

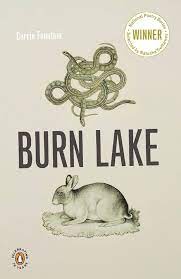

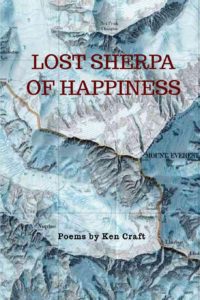

- “An Old Man Walking Dawn’s Borders (from Lost Sherpa of Happiness) This is my “dark horse” choice — the kind of poem you wouldn’t initially think of reading, but then, the more you look at it, the more you say, “Why not? I feel kind of sorry for this old man. Let’s share his story by giving him a mic!”

- “Into the Urban” (from Lost Sherpa of Happiness) Ready for a memory poem? Memories are one of the most valuable resources a poet has at his disposal. This one takes readers to the city of Hartford, CT, when I was a kid visiting my great-grandparents’ apartment.

- “When Babcia Caught Her Breath” (from Lost Sherpa of Happiness) From the city to a Maine lake, and my how time flies, as this one concerns my grandmother visiting the wilds of Maine for the first time. The whole poem was built on the last line, which were words she actually said — ones that I will never forget.

- “Lost Sherpa of Happiness” (from Lost Sherpa of Happiness) The title poem tips its simple hat to Buddhism, which, along with Taoism, has influenced a lot of my work. If listeners like it, they’ll know there is plenty more where this came from.

- BONUS POEM (from Lost Sherpa of Happiness) I have a few ready if time allows, but I’m sharing the mic with two other poets, so time will be a taskmaster laying down some discipline — always a good thing.

Hey. I’ll let you know how it goes!