The best cure for writer’s block is the writer herself. Consider, writer, your field of expertise. Within the goal lines you will surely find these players: self, ego, and consciousness. Now jump in the stream and, as the psychologists say, let yourself go.

If you do, and you start with the prompt “I always have to be…,” you might come up with a poem like Ron Padgett’s “Think and Do” below. It looks easy, reading it, and nothing inspires an idea-hungry writer like the sensation of looking easy.

From a few things that define you as a person, you just relax on your back and let the stream of consciousness carry you down river. Enjoy the muffled sounds of forest and rushing river (your ears are underwater) and especially the moving sky and clouds above you, framed like art by treetops.

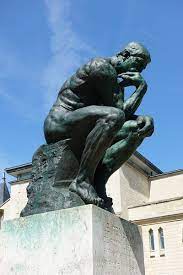

Before you know it, your sense of humor will kick in (it always does once you’re relaxed). And before you know it, you’ve gone from stuff you’re good at to non sequiturs. You know, like Rodin’s The Thinker, a big lug of a statue that holds within its muscular body all manner of contradiction.

By spicing your self-analysis with specificity and thought processes that your friends, upon reading them, would say, “Yeah, that’s just like him,” you’ll have a lively poem to work on in no time.

Looks easy, right? (Cardinal rule for writer’s block: Bring a sense of humor.)

Think and Do

Ron Padgett

I always have to be doing something, accomplishing some-

thing, fixing something, going somewhere, feeling purposeful,

useful, competent—even coughing, as I just did, gives me the

satisfaction of having “just cleared something up.” The phone

bill arrives and minutes later I’ve written the check. The world

starts to go to war and I shout, “Hey, wait a second, let’s think

about this!” and they lay down their arms and ruminate. Now

they are frozen in postures of thought, like Rodin’s statue, the

one outside Philosophy Hall at Columbia. His accomplish-

ments are muscular. How could a guy with such big muscles be

thinking so much? It gives you the idea that he’s worked all his

life to get those muscles, and now he has no use for them. It

makes him pensive, sober, even depressed sometimes, and

because his range of motion is nil, he cannot leap down from

the pedestal and attend classes in Philosophy Hall. I am so

lucky to be elastic! I am so happy to be able to think of the

word elastic, and have it snap me back to underwear, which

reminds me: I have to do the laundry soon.