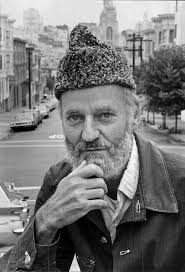

If you want to darn another hole in your poetry sock, you might try the once-famous Lawrence Ferlinghetti. You could even cheat by reaching for his “Greatest Poems” — though you could argue that editor Nancy J. Peters’ choices for “greatest” are as suspect as Lee Harvey Oswald. What can I say? On the savanna of literature, Subjectivity is King of the Beasts (and I ain’t lion).

If you cringed at that pun, you might cringe at a few of Ferlinghetti’s, too, because he wasn’t above dropping them into his poems. Not that he loses points with me for using them. I am a fan. Every time the groaners start acting superior about them, I point to the Bard, who was a master of puns himself, only in his case, said puns were labeled “great literature.”

I would say it’s a funny world, but let’s just say it’s a funny savanna.

If this collection of “greatest hits” was a hamburger, I would be a carb guy. Meaning, the early poems and late poems (buns, if you’re still with me) seemed more entertaining than all the middle protein (burger, medium rare). I would even lean toward the earliest as the better.

Some enjoyable turns of phrases I wrote down in my journal from the early stuff (as is my habit) are the following:

loud dark winter

burnt places of that almond world

poet’s plangent dream

algebra of lyricism

leaf in a pool…lay like an eye winking circles

silence hung like a lost idea

groaning with babies and bayonets under cement skies

No, not show stoppers, but still, enough to snag the eye before the stream of lyricism pulls them loose and continues them on their way.

As for the middle of the greatest hits sandwich, I was a bit underwhelmed at times. Not much special in the way of metaphor or imagery. Ferlinghetti’s go-to’s seem to be alliteration and assonance, but he was happy to ignore those, too, once he became popular (popularity being the Get Out of Jail Free card in Poetry World, that most strange and wonderful and insulated world known to man).

Here, for example, is LF riffing casually (it certainly seems) on underwear, a subject every poet should write about:

Underwear

Lawrence Ferlinghetti

I didn’t get much sleep last night

thinking about underwear

Have you ever stopped to consider

underwear in the abstract

When you really dig into it

some shocking problems are raised

Underwear is something

we all have to deal with

Everyone wears

some kind of underwear

The Pope wears underwear I hope

The Governor of Louisiana

wears underwear

I saw him on TV

He must have had tight underwear

He squirmed a lot

Underwear can really get you in a bind

You have seen the underwear ads

for men and women

so alike but so different

Women’s underwear holds things up

Men’s underwear holds things down

Underwear is one thing

men and women have in common

Underwear is all we have between us

You have seen the three-color pictures

with crotches encircled

to show the areas of extra strength

and three-way stretch

promising full freedom of action

Don’t be deceived

It’s all based on the two-party system

which doesn’t allow much freedom of choice

the way things are set up

America in its Underwear

struggles thru the night

Underwear controls everything in the end

Take foundation garments for instance

They are really fascist forms

of underground government

making people believe

something but the truth

telling you what you can or can’t do

Did you ever try to get around a girdle

Perhaps Non-Violent Action

is the only answer

Did Gandhi wear a girdle?

Did Lady Macbeth wear a girdle?

Was that why Macbeth murdered sleep?

And that spot she was always rubbing—

Was it really in her underwear?

Modern anglosaxon ladies

must have huge guilt complexes

always washing and washing and washing

Out damned spot

Underwear with spots very suspicious

Underwear with bulges very shocking

Underwear on clothesline a great flag of freedom

Someone has escaped his Underwear

May be naked somewhere

Help!

But don’t worry

Everybody’s still hung up in it

There won’t be no real revolution

And poetry still the underwear of the soul

And underwear still covering

a multitude of faults

in the geological sense—

strange sedimentary stones, inscrutable cracks!

If I were you I’d keep aside

an oversize pair of winter underwear

Do not go naked into that good night

And in the meantime

keep calm and warm and dry

No use stirring ourselves up prematurely

‘over Nothing’

Move forward with dignity

hand in vest

Don’t get emotional

And death shall have no dominion

There’s plenty of time my darling

Are we not still young and easy

Don’t shout

As you can see, Ferlinghetti forgoes periods and commas, though he does employ capitalization, which is more than some modern poets do, and other punctuation marks make cameos, too. Getting edgy, in other words, but not going over the edge.

Overall, a fun poet but, like Frank O’Hara, probably not one to imitate (unless you truly understand the meaning of that sign at the edge of a dark wood, “Imitate at Your Own Risk”).