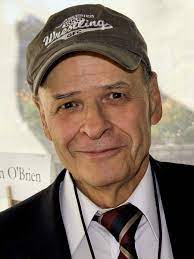

Novelist and short story writer Tim O’Brien’s Dad’s Maybe Book, is an advice manual of sorts addressed to his two sons, Timmy and Tad. In it, he offers advice to the boys about life. Luckily for writers, he also offers the boys advice on writing. You never know, I figure he’s thinking, if genes will carry.

Below is an O’Brien riff on the writer’s trap known as explaining too much. And though O’Brien uses the words “fiction” and “stories,” you can bet the advice works as well for poetry, drama, and nonfiction. Here’s O’Brien:

“The essential object of fiction is not to explain. Explanation narrows. Explanation fixes. Explanation dissolves mystery. Explanation imposes artificial, arrogant order on human contradictions between fact and fact. The essential object of fiction is to embrace and widen and deepen all that is unknown and unknowable—who we are, why we are—and to offer us late-night company as we lie awake pondering our universal journey down the birth canal, and out into the light, and then toward the grave.

“In a story, explanation is like joining a magician backstage. The mysterious becomes mechanical. The miracle becomes banal. Delight vanishes. Wonder vanishes. What was once surprising, even beautiful, devolves into tired causality. One might as well be washing dishes.

“Imagine, for instance, that Flannery O’Connor had devoted a few pages to explaining how the Misfit became the Misfit, how evil became evil: the Misfit was dyslexic as a boy; this led to that—bad grades in school, chips on his shoulder. Pile on the psychology. Even as explanation, and because it is explanation, there would be, for me, something both fishy and aesthetically ugly about this sort of thing, the stink of determinism, the stink of false certainty, the stink of a half- or a quarter-truth, the stink of hypocrisy, the stink of flimflam, the stink of pretending to have sorted out the secrets of the human heart. Moreover, Timmy and Tad, I want you to bear in mind that explanation doesn’t always explain. Few dyslexics end up butchering old ladies. Evil is. In the here-and-now presence of evil, evil always purely is, no matter how we might explain it. Ask the dead at My Lai. Ask the Misfit. ‘Nome,’ he says. ‘I ain’t a good man.’ In the pages of ‘A Good Man Is Hard to Find,’ Flannery O’Connor goes out of her way to satirize and even to ridicule such explanation. And for Hemingway, too, explanation is submerged below the waterline of his famous iceberg. In great stories, as in life, we are confronted with raw presence. Events don’t annotate themselves. Nightmares don’t diagnose themselves. With the first whiff of Zyklon B, with the first syllables of a Dear John letter, with the first ting-a-ling of a dreaded phone call, with the first glimpse of your own nervous oncologist, there is what purely is.”