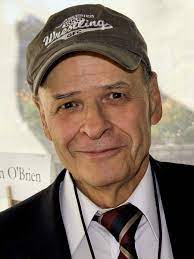

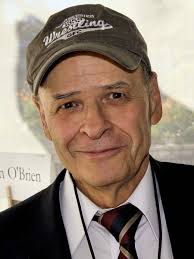

In Dad’s Maybe Book, author Tim O’Brien spells out some rules for writing intended for his sons, Tad and Timmy. They are equally intended for the reader, who is serving as a vicarious child of the O’Briens reading along.

Below are 14 Rules O’Brien shares, directly quoted from the book, and though he says “story” now and then, I daresay the advice works for poetry, novels, plays, and essays as well.

See if you agree:

1. Review the difference between “lie” and “lay.” A good number of TV personalities, politicians, poets, recording artists, newspaper columnists, pediatricians, and crime writers should do the same.

2. Do not be terrified of emotion. Be terrified of fraudulence.

3. Stories are not puzzles. Puzzles are puzzles.

4. Information is not story. Information is information.

5. Pay close attention to the issue of simultaneity. In life, as in a good story, numerous things occur at the same time, even when your attention might be riveted on a rattlesnake coiled to strike. In other words, when you’re writing stories, do not juggle only a single ball. (Single ball jugglers rarely get hired twice to entertain at birthday parties.) Fill your stories with “nice contradictions between fact and fact.” Fill your stories with food and drink, the weather, tired feet, dental appointments, phone calls from out of the blue, upset stomachs, flat tires, pens that run out of ink, undelivered letters of apology, traffic jams, swollen bladders, and spilled coffee. These and other intrusions must be endlessly juggled as we make our way along the story lines of our lives. Therefore, don’t insulate your characters from the random clutter that distracts and infuriates and entertains all of us.

6. Similarly, do not let excessive plotting ruin your story anymore than you would allow it to ruin your life.

7. Bear in mind that stories appeal not only to the head, but also to the stomach, the back of the throat, the tear glands, the adrenal glands, the funny bone, the nape of the neck, the lungs, the blood, and the heart—the whole human being.

8. You are writing not only for your contemporaries. You are writing also for a seventeen-year-old student who might encounter your story two hundred years from now, or for an old man in Denmark in the year 2420, or for a lonely widow sitting at a futuristic slot machine in the year 4620.

9. Also, believe it or not, you are writing for those who have preceded you— for Thomas Jefferson, for the children of Auschwitz, and for a father who may no longer be present to read your story.

10. Surprise yourself. You might then surprise your reader.

11. Do not fear (or deny) your own ignorance. It makes for curiosity.

12. Do not fear (or deny) ambiguity. Though the prose itself may be crystalline, good stories almost always involve people snagged up in confusing moral circumstances. Think of Raskolnikov. Think of Charles and Emma Bovary. Think of your dad.

13. Pay attention to every word. There are twenty-six letters in the English alphabet, plus a few punctuation marks. Those twenty-six letters, if poorly arranged, will result in mediocrity, infelicity, or plain gibberish. But from those same twenty-six letters, well arranged, come the sonnets of Shakespeare. The letters of the alphabet can be likened to the four chemical bases—adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine—that constitute the building blocks of all plant and animal DNA. The precise sequence, or order, of the bases determines whether an organism becomes a polar bear or a dachshund or William Shakespeare. Therefore, along the same lines, I suggest you do all you can to arrange the letters of the alphabet in exacting sequences.

14. Read your writing aloud. Does it make sense? Does it make music?