As a kid reading Jonathan Swift’s classic, Gulliver’s Travels, I marveled not so much at the Lilliputians as at the Houyhnhnms, that society of horses blessed with reason—a society far above the Yahoos, Swift’s derisive name for humankind.

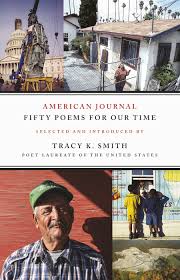

It all came back to me as I read Ross Gay’s wonderful poem, “becoming a horse,” in Tracy K. Smith’s collection, American Journal: Fifty Poems for Our Time.

It contained lovely ideas, such as the poet becoming “a snatch of grass in the thing’s maw” or “a fly tasting its ear.” It contained lovely concepts, such as the poet coming to know the world as a horse knows it: “the sorrow of a brook creasing a field,” “the small song in my chest,” “the slow honest tongue.” All that from the simple act of “putting my heart to the horse’s.”

Empathy. The world through another’s eyes—even another creature’s eyes. More than anything, it teaches us the sorrow of being human. Don’t believe me? See for yourself:

becoming a horse

by Ross Gay

It was dragging my hands along its belly,

loosing the bit and wiping the spit

from its mouth made me

a snatch of grass in the thing’s maw,

a fly tasting its ear. It was

touching my nose to his made me know

the clover’s bloom, my wet eye to his

made me know the long field’s secrets.

But it was putting my heart to the horse’s that made me know

the sorrow of horses. The sorrow

of a brook creasing a field. The maggot

turning in its corpse. Made me

forsake my thumbs for the sheen of unshod hooves.

And in this way drop my torches.

And in this way drop my knives.

Feel the small song in my chest

swell and my coat glisten and twitch.

And my face grow long.

And these words cast off, at last,

for the slow honest tongue of horses.

As a writer, you might try it yourself: becoming a dog, a red fox, an owl—whatever stirs the wonder and sadness in you. It is an exercise in empathy and beauty.