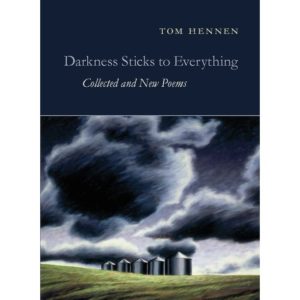

As a Midwestern poet, Tom Hennen is often paired in people’s minds with Ted Kooser. That is, if Hennen is in your mind in the first place. For me, he wasn’t because I’d never heard of him, and while his poetry is, like Kooser’s, plain-spoken, it is also so nature-centric that I cannot in good faith consider these two that similar. Related by geography and style at times, but different, too.

First and foremost, if you crave rapidly-disappearing nature as a topic in your poetry, Hennen is your man. By modern standards where identity serves as the new Garden of Poetic Eden, he is quaint with his love of the four seasons (especially autumn), trees (especially pines), earth (especially its sky) and so much more. This collection, encompassing some of his best work along with some new poesies, includes the early image poems, focused with great specificity on the landscape, as well as his wonderful collection of prose poems covering the same matter, called “Crawling Out the Window.”

If you are looking for comparisons, Hennen’s quiet army of fans are more than willing to provide them. The Ancient Chinese poets. Robert Bly. James Wright. Francis Ponge. The Scandinavian poets Olav H. Hauge, Harry Martinson, and Rolf Jacobsen. Imagery, personification, and folksiness work together to bring big surprises in small packages. As you read Hennen, his poems grow on you like moss on a tree. Slowly.

So let’s look and see, shall we?

Spring Follows Winter Once More

Lying here in the tall grass

Where it’s so soft

Is this what it is to go home?

Into the earth

Of worms and black smells

With a larch tree gathering sunlight

In the spring afternoon

And the gates of Paradise open just enough

To let out

A flock of geese.

Finding Horse Skulls on a Day That Smelled of Flowers

At the place where I found the two white skulls

Sunlight came through the aspen branches.

Under one skull were

Large beetles with hard bodies.

The other one

I didn’t move.

Around them new grass grew

Making the scent of the earth visible.

Where the sun touched shining bone

It was warm

As though the horses were dreaming

In the spring afternoon

With night

Still miles away.

Things Are Light and Transparent

During the fall, objects come apart when you look at them.

Farm buildings are mistaken for smoke among the trees.

Stones and grass lift just enough off the ground so that you can

see daylight under them. People you know become transparent

and can no longer hide anything from you. The pond the

color of the rainy sky comes up to both sides of the gravel road

looking shiny as airplane wings. From it comes the surprised

cry the heron makes each time it finds itself floating upward

into a heaven of air, pulled by the attraction of an undiscovered

planet.

The Life of a Day

Like people or dogs, each day is unique and has its own personality

quirks, which can easily be seen if you look closely.

But there are so few days as compared to people, not to mention

dogs, that it would be surprising if a day were not a hundred

times more interesting than most people. Usually they

just pass, mostly unnoticed, unless they are wildly nice, such

as autumn ones full of red maple trees and hazy sunlight, or

if they are grimly awful ones in a winter blizzard that kills the

lost traveler and bunches of cattle. For some reason we want

to see days pass, even though most of us claim we don’t care to

reach our last one for a long time. We examine each day before

us with barely a glance and say, no, this isn’t one I’ve been looking

for, and wait in a bored sort of way for the next, when, we

are convinced, our lives will start for real. Meanwhile, this day

is going by perfectly well adjusted, as some days are, with the

right amounts of sunlight and shade, and a light breeze perfumed

from the mixture of fallen apples, corn stubble, dry oak

leaves, and the faint odor of last night’s meandering skunk.

Like I said, nothing fancy here. Country wisdom by a man who can name things and who sees movement and life in ways that we don’t and in things that we don’t. Like a warm breeze in early spring, it is. If you’re a certain kind of “old soul” reader, that is.