Voice. It’s that magical, magnetic je ne sais quoi that draws us. To people, yes. But to writing, too: artists heard through the medium of paper and ink.

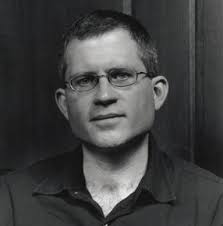

From the earliest pages of Christian Wiman’s book He Held Radical Light, I found myself attracted to the voice. To me, it seemed the voice of reason. Balanced, yet opinionated. Informed, yet informal.

And the biggest test of all? I found myself liking most of the poems that meant a lot to Wiman. As Facebook and Twitter have proven (though not to me, as I avoid both like the plague), there’s nothing people like better than listening to a sermon from the choir.

On the first page, in the first sentence, we find Wiman reading the letters of A. R. Ammons “who for years sowed and savored his loneliness in lonely Ithaca, New York.” This leads to an Ammons poem, the one that would lend Wiman a title for his collection of short essays. Let’s listen in:

THE CITY LIMITS

by A. R. Ammons

When you consider the radiance, that it does not withhold

itself but pours its abundance without selection into every

nook and cranny not overhung or hidden; when you consider

that birds’ bones make no awful noise against the light but

lie low in the light as in a high testimony; when you consider

the radiance, that it will look into the guiltiest

swervings of the weaving heart and bear itself upon them,

not flinching into disguise or darkening; when you consider

the abundance of such resource as illuminates the glow-blue

bodies and gold-skeined wings of flies swarming the dumped

guts of a natural slaughter or the coil of shit and in no

way winces from its storms of generosity; when you consider

that air or vacuum, snow or shale, squid or wolf, rose or lichen,

each is accepted into as much light as it will take, then

the heart moves roomier, the man stands and looks about, the

leaf does not increase itself above the grass, and the dark

work of the deepest cells is of a tune with May bushes

and fear lit by the breadth of such calmly turns to praise.

From here, Wiman gets into anecdotes about listening to Ammons do a memorable (for the wrong reasons) poetry reading. Then to 80-year-old Donald Hall’s scary admission, “I was thirty-eight when I realized not a word I wrote was going to last.” Those words gave Wiman a “galactic chill.” For a writer—especially a young writer—it’s like walking willingly into that dark night.

Which of course puts Wiman onto his themes for this book. Or shall I say its dichotomies: religion vs. atheism, fame vs. obscurity, faith vs. art. He offers up two looks at the same chasm: Jack Gilbert’s and Mark Strand’s. Here are the two poems, a bracing start for your Sabbath Day morning with Wiman’s commentary in between:

They will put my body into the ground.

Chemistry will have its way for a time,

and then large beetles will come.

After that, the small beetles. Then

the disassembling. After that, the Puccini

will dwindle the way light goes

from the sea. Even Pittsburgh will

vanish, leaving a greed tough as winter.

—JACK GILBERT

Wiman comments: “What is it we want when we can’t stop wanting? I say God, but Jack Gilbert’s greed may be equally accurate, at least as long as God is an object of desire rather than its engine, end rather than means. Gilbert’s poem amounts to a kind of metaphysics for materialists. Something survives us, the poem suggests, some cellular imperative ravening past whatever cohesion kept us, us; some life force that is suspiciously close to a death force: it’s winter, after all, and not any ordinary winter but one from which even Puccini and Pittsburgh have vanished, an ur-winter, you might say, even a nuclear one. Of course on the literal level the poem is referring to the way information dies out in one man’s brain—Gilbert was actually from Pittsburgh, and I assume he loved Puccini—but the end of the poem reverberates in a way that is both beautiful and terrible. When you are ending, it can seem like everything is, and the last task of some lives is to let the world go on being the world they once loved. But what song—or what but song—can contain that tangle of pain and praise?”

Then comes the example of Mark Strand, who sheds some light on love. A love, perhaps, you haven’t thought of.

A.M.

by Mark Strand

. . . And here the dark infinitive to feel,

Which would endure and have the earth be still

And the star-strewn night pour down the mountains

Into the hissing fields and silent towns until the last

Insomniac turned in, must end, and early risers see

The scarlet clouds break up and golden plumes of smoke

From uniform dark homes turn white, and so on down

To the smallest blade of grass and fallen leaf

Touched by the arriving light. Another day has come,

Another fabulous escape from the damages of night,

So even the gulls, in the ragged circle of their flight,

Above the sea’s long lanes that flash and fall, scream

Their approval. How well the sun’s rays probe

The rotting carcass of a skate, how well

They show the worms and swarming flies at work,

How well they shine upon the fatal sprawl

Of everything on earth. How well they love us all.