Why do so many metaphors speak the language of violence?

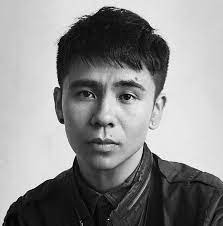

That question occurred to Ocean Vuong as he was writing his “novel” that walks and talks like a memoir, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. Though many examples abound, Vuong chose just a few as shown in this excerpt:

“But why can’t the language for creativity be the language of regeneration?

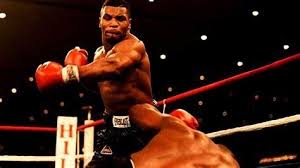

“You killed that poem, we say. You’re a killer. You came in to that novel guns blazing. I am hammering this paragraph, I am banging them out, we say. I owned that workshop. I shut it down. I crushed them. We smashed the competition. I’m wrestling with the muse. The state, where people live, is a battleground state. The audience is a target audience. ‘Good for you, man,’ a man once said to me at a party, ‘you’re making a killing with poetry. You’re knockin’ ’em dead.'”

I have heard of metaphors for violence being essential in the language of sports, but here it creeps into creativity, the arts, everyday language itself. Do we even notice it, though? If not, then metaphor has assumed its place in our language, no longer looking like a comparison in glasses and wig, but acting like a thing unhidden itself.

On Earth We’re Briefly Violent, maybe? Even if it’s not with sticks and stones but with those legendary “words that will never hurt me.”