When your average reader thinks of the word “poetry,” he doesn’t think of the word “macho” at the same time. And yet, macho poetry exists. That is, if you’re willing to bend “macho” from its negative connotations and tag along instead with Edward Hirsch’s description of Edgar Kunz’s Tap Out – “gutsy, tough-minded, working-class poems of memory and initiation.”

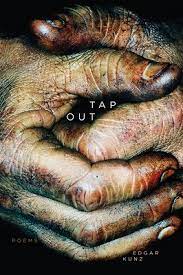

Then there’s Tap Out’s cover. A man’s hands clasped. True, they’re so greasy they look less like a wrestler’s hands than a miner’s or auto mechanic’s, but they certainly convey the idea. What’s most important, though, are the poems in this 2019 outing. Y-chromosome or no, many are damn good.

For instance, Kunz mines the tried and true (for poets) territory of an alcoholic, abusive father to good effect. I was especially taken with “Close,” which originally appeared, appropriately enough, in Narrative magazine.

Close

Off early from B&R Diesel, sharp

with liquor and filtered Kings, he drifts

across the double-yellow, swings

into an iced-over lot. He runs me through

the basics: K-turn, parallel, back-in.

Jerks the Sierra into reverse and eases

the bumper up against the side

of the old bank building. We meet

at the end of the loaded bed, exhaust

and brakelight pooling around our knees.

He balls the front of my coat in his fist,

pulls me close to show the distance

between bumper and brick, pulls hard

until I’m up against the slender arc

of his collarbone, the fine dark stubble

shading his jaw, his hollowed-out cheeks.

He’s still beautiful, my father. Fluid.

Powerful. His bare forearms corded

with muscle, bristling in the cold. Yes,

he’s drunk. Yes, I have already begun the life-

long work of hating him, a job

that will carve me down to almost

nothing. I have already begun to catalog

every way he has failed me. Yes.

And here he is. Home early from a day shift

in Fall River. Teaching me what I need

to know. Pulling me roughly toward him,

the last half-hour of sunlight blazing

in his face, saying This is how close

you can get. Asking if I can see it.

If I know what he means. Saying This. This

close. Like this.

Like many poems in this collection, a narrative poem told with economy. A vivid snapshot in time. “Close” is particularly powerful thanks to the turn that begins with the line “He’s still beautiful, my father” – not words you’d expect from a teen whose father has him by the fist. And that bit about “the life- / long work of hating him, a job / that will carve me down to almost / nothing.” Whew. It’s lines like this that leave me wondering why there are so many readers who do not bother reading poetry, for it is only poetry that can deliver rabbit-punches like this. What these readers are missing!

While still on my heels from reading “Close,” I turned the page and read “After the Attempt,” which appeared originally in Gulf Coast. In this case, it was the closing that wowed me. Kunz nails the landing, as they say. Even the Russian judge is forced to say as much.

After the Attempt

They took your shoelaces,

your carabiner of tooth-

edged keys, but left you

your belt, which you cinched

over your loopless scrubs.

They shaved your scalp

for the stitches but missed

a tuft above your ear

that catches the light

from the hingeless windows.

The receptionist holds up

a small paper bag

stapled shut. Whatever

you had worth saving.

You look, then look away.

Once, hungover

on a gut-and-remodel job

in Grafton, you cracked the root

of your nose with your claw

hammer’s backswing.

You stood very still after,

watching your blood scatter

on the plywood floor, alien

and bright as coins

from a distant country.

I don’t know about you, but I was bought and sold on that blood money at the end. Great image. It didn’t hurt that the familiar worked for it, too. Assuming the setting was Grafton, Massachusetts, this was only a town over from where I lived for twenty years.

In the end, I guess you can say this. There’s not a lot of “macho poetry” out there, and when there is, it’s not always worth reading. In the case of Edgar Kunz’s collection, however, another story. Another story entirely.