It seems fitting that Tony Hoagland’s farewell book to the world would tackle the concept of voice. If any poet knew of what he spoke, Hoagland was the man. Whether you read his poems or his sage essays about poems or writing poetry, you “heard” Hoagland and felt as if you were lucky to have found an open seat in his seminar.

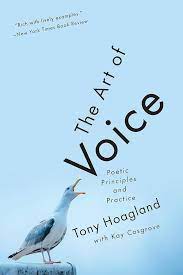

The last seminar you can attend is The Art of Voice: Poetic Principles and Practice. The posthumous collection of essays stands as a short, “Hey, wait a minute,” on the matter of hard and fast rules about poetry writing. Chief among them? Your poetry must be as concise as possible to succeed.

The old adages sound logical, but Strunk and White weren’t poets, either. What about voice? With due diligence, Hoagland demonstrates that voice often requires colloquialisms, idioms, asides, etc. — the stuff that leavens our daily speech.

If executed with purpose, voice quickly bonds writer with reader, who is more than willing to forgive linguistic excess in exchange for a temporary soul mate capable of providing an insight or two on the world.

Hoagland provides many examples of poems, some complete and others frustratingly not, to back up his words. Here’s an excerpt he uses from Lisa Lewis’s poem, “While I’m Walking”:

Once I saw a man get mad because two people asked him

The same question. The second didn’t even know of the

first;

Anyone would’ve called the man unfair, unreasonable,

He stormed at the person who approached him

That unfortunate second time, and it was nothing,

Where’s the restroom? or Where could I find a telephone?

He was a clerk, and the second person, a shopper,

suggested

He “change his attitude”…

But though it ruined their day it improved mine, I could rest

Less alone in anger and wounded spirits. That was long ago,…

Hoagland comments, “Lewis’s plain linguistic style might be described as ‘prosaic,’ that is, verbose and unpoetic, yet it compels us because her speaker tells more truth than we usually get, and she does so with a bluntness that tests the conventions of decorum. Lewis is a narrative-discursive poet in style, not a poet of lyrical language, but there is a rhythmic, businesslike terseness in her storytelling and thinking that is riveting in is purposeful informality. Her speaker captivates us for the duration of whatever she wants to say. That’s what a voice poet wants to do: hook us and then escort us deep into the interior of the poem, which is also the interior of the poet, which is also the interior of the world.

“In a world where, socially, we often feel stranded on the surface of appearances, people go to poems for the fierce, uncensored candor they provide, the complex, unflattering, often ambivalent way they stare into the middle of things. In a world where, as one poet says, ‘people speak to each other mostly for profit,’ it is exhilarating to listen to a voice that is practicing disclosure without seeking advantage. That is intimate.”

And so the book leaves practitioners with an oxymoron of sorts. For voice, the poet must practice her intimacy, plan her informality, execute her natural voice for a casually-preconceived cause.

There are some writing exercises at the back of the book, if you wish. And some reader-writers will dive in. But others, like me, will find the book’s encouragement enough. Rereading a 168-page book is an exercise of sorts, too.

Either way, you’ll leave the book realizing that there are more angles than you thought to “voice,” and more “types” of voice, too, such as “speech registers” and “imported voices” and “voices borrowed from the environment.”

Bottom line? Strunk and White were fine for your college freshmen writing course, but maybe not for your poems. Perhaps it’s time to make like Pygmalion and give voice to your art.