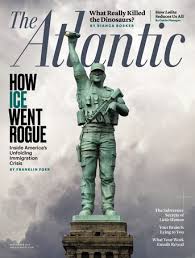

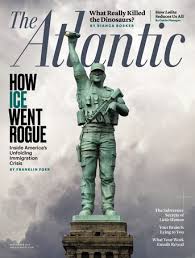

The September 2018 issue of The Atlantic — a bit briny as usual — just beached itself in my mailbox and lo, there was a feature article on poetry in it! What’s more, it’s headline proclaimed (“Dewey Wins!”-like) “How Poetry Came to Matter Again.” Which means, in case you haven’t been paying attention, that poetry hasn’t really mattered at all. Up until now, I mean.

For full appreciation, you should read Jesse Lichtenstein’s article yourself. I can sum up its main points, however. The Pearly (Very, Very White) Gates have been stormed. Like Lazarus, poetry has been brought back to life, most probably by a dark-skinned, female, transgender Jesus.

Meaning: We owe a debt of gratitude to the very people our wonderful president Donny (and president of vice, Mikey) have little use for: immigrants, minorities, LGBTQ, and females.

This should come as no surprise to people peddling their poetry. In their submission write-ups, many markets make special points of soliciting work from these writers. This article clarifies why. New blood. New life. New voices. All good, especially if it makes poetry appealing to young readers and listeners, all but forgotten by poets of the past.

Also getting shout-outs in Lichtenstein’s article? Spoken word and performance poetry. Old-school types may be writing their poetry under bushels, sharing only with each other in the shadows of their critiquing covers before sending poems out along the traditional poetry highways to poetry magazines and poetry publishers, but the new schoolers are taking the road more digitally traveled.

They’re taking their poetry public to ITube, YouTube, and WeTube; to podcasts, Instagram, and open mics. They’re truly out there. Self-promoting, self-proclaiming, self-advocating. As Exhibit A, I need only say two words: “Rupi” and “Kaur” (or, as she is known in some poetry circles: “best” and “seller”).

Me, I am new to the poetry-writing world and have found it very tight indeed. Protective circles, the higher you go. Fellow back-scratchers. M’s, F’s, and A’s, sprinkled with teacher-poet’s pets who promote their proteges.

This does not make me a minority in the classic sense. It just makes me a (ahem) “seasoned” white guy who only merits the title “minority” as an “outsider.”

That’s OK, though. I took heart that this article promoted a renewed acceptance of the pronoun “I” and how new voices are unabashedly embracing it. I’ve written about the pronoun “I” and poetry before, if you’re a pronoun fan.

It’s also important to remember that, no matter what our backgrounds or identities, we are all similar in our humanity, though separate in our unique mortal coils, each built by unique histories.

In that sense, we are all immigrants to the world, all conscripted against our wills to our finite lives, all capable of speaking to readers no matter what their age, race, sex, or gender identity.

I like to think, at least.

So the lesson of the article is this: Poetry is not an ivory tower, it is a big tent. Poetry belongs to the people, and the people can be reached in new and unique ways.

What’s more, poetry does not and should not belong to select cliques. This includes poetry pecking orders. They should be toppled like statues of Stalin. Yet poets, young AND old, talented and published, still stick to promoting only their friends and writers they consider their equals.

If you want to write for yourself, that’s cool. For me, though, poetry without readers is like speakers without listeners. A supreme form of solipsism.

As JFK might have put it, then: Ask not what poetry can do for you; ask what you can do for poetry. Audiences are out there and waiting.