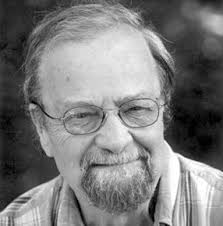

In the summer of 2018, we lost another writer of note in Donald Hall, a New England poet and essayist whose roots ran deep into the hills of New Hampshire. Hall and Jane Kenyon, as husband and wife, made for one of the most prolifically poetic marriages you could imagine. Sadly, Kenyon’s production was cut short by leukemia. Hall, on the other hand, lived to 89–long enough to have his say in poetry and even to jump genre ships by experimenting a bit with essays.

I recently purchased his book, The Selected Poems of Donald Hall, which features “My Son My Executioner” as its lead-off batter:

My Son My Executioner

by Donald Hall

My son, my executioner,

I take you in my arms,

Quiet and small and just astir

And whom my body warms.

Sweet death, small son, our instrument

Of immortality.

Your cries and hungers document

Our bodily decay.

We twenty-five and twenty-two,

Who seemed to live forever.

Observe enduring life in you

And start to die together.

It’s a rather succinct and unexpected look at one of literature’s universal themes: death. Here it is embodied in the unusual swaddling of life. Not only life, but life at its earliest incarnation, when it seems most beautiful, most sweet, most immortal.

Hall uses this little package of wonder as a startling memento mori, which is an old Latin term for reflecting on your mortality. In the medieval Christian church, it might take the form of a human skull. Consider, for instance, the many artistic renditions of St. Jerome, almost always at his scholarly work with a skull on his desk. As Exhibit B, I give you Act V, Scene 1, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, where the protagonist holds a skull aloft and proclaims, “Alas, poor Yorick, I knew him, Horatio, a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy.”

Hall pulls the rug from under his readers by exchanging the narrator’s son for tradition’s skull. If, as husband and wife, you just gave birth to a beautiful boy, it’s yet another milestone marking the shortening wick of your life. Another tick on the clock of mortality.

In stanza two, we get the unusual word pairing of “Sweet death, small son” followed by “our instrument of immortality.” Children, then, as reminders of where we came from and where we will go. If they embody immortality, how can we claim to be the same when we are so different?

The last stanza hoists the narrator and his wife’s delusions on their petards: “We twenty-five and twenty-two, / Who seemed to live forever….” Mid-twenties, it would seem, is as far from death as two-hours old. But holding a newborn is proof that one generation cometh so another can passeth (I’m getting all Ecclesiastes on you now). We fool ourselves by acknowledging death (of course) while supposing it is something that happens to others, not ourselves.

What I like about Hall’s poem is its simplicity. Its theme is directly stated. The power comes from its crying, burbling surprise looking up at his daddy: not so much, “It’s a boy!” but “It’s a reminder!”

The generations grind on, and with them, our days….